Tenaya

August

2015

Part Three

Northern Albania

| |

| HOME |

| About Tenaya |

| About Us |

| Latest Update |

| Logs from Current Year |

| Logs from Previous Years |

| Katie's View |

| Route Map |

| Links |

| Contact Us |

![]()

10 August 2015

Shengjin Harbor

41 48'.79N : 019 35'.36E

It's a good thing we're not overly concerned about where we moor our boat. Tenaya sits askew, tied to the new ferry dock in the Port of Shengjin. The built-in rubber bumpers are spaced well for a large ship, not for a 40 foot sailboat.

The ferry came a few times but it stopped. Nobody could tell us why. Perhaps the sewery stench emanating from grates along the dock, or the fish processing plant just beyond, might be the cause. Or maybe it was the soot that blows in from somewhere and forms drifts on our deck, or the nightly mosquito raids...

In spite of all this, we enjoyed our time in Shengjin most of all. We only left when the harbormaster told our agent, Frrok Frroku, we'd been there too long.

Shengjin, the northernmost port in Albania, is located at the head of a large open bay. The river Drini flows through wetlands and into the Adriatic just to the south, creating a wealth of fish. Shengjin has been a fishing town for more than 1,000 years and the port is still home to a fishing fleet. There is also a transfer station where cargo carriers deliver cement to a facility ashore to be loaded onto trucks.

Once Tenaya was secure with spring lines, fenders, and an old t-shirt to protect her white bow from the black rubber bumper, Jim met Frrok at the coffee bar to give him our ship's papers and ask about renting a car. Frrok said he'd see what he could do and let us know the next morning. Niku overheard the conversation and offered to take us to his family's home in Tropoja high in the mountains. Perfect!

Lezha

Our first stop was the 14th century cathedral of Saint Nicholas in Lezha where Skanderbeg, a national hero, was buried. His bones are no longer here, but there is a tomb-like memorial and a bust of the man who kept the Ottoman Empire at bay until his death.

Next we went to the castle on the hill which was part of Skanderbeg's defense system. What a fantastic view of Lezha, the surrounding farmland, and the wide estuary below!

"My father will come with us because you'll be safer than with just me," Niku said. His father had been in the military in Tropoja, in northeastern Albania, during the Communist regime.

Jim and I rode in the comfortable, breezy backseat as Niku and his father chatted away the miles. Farmland gave way to foothills and eventually we reached the lake at Vau e Dejes, one of three lakes created when a massive hydroelectric project was built in the 1970s. The lake just above it, Komani Lake, was our next destination.

Traffic stopped just inside a narrow tunnel. Niku's dad hopped out and disappeared. Jim and I followed and were surprised to find a small parking area and a large ferry outside. At noon Niku drove his car onto the Alpin ferry for the two hour, 25 mile, ride up Lake Komani.

Sheer cliffs, rocky precipices, and mountains blanketed in green drop directly into the shimmering blue-green water. Some gorges were so narrow that it seemed if we stretched out our arms, we'd touch the stone. If this ferry ride was anywhere else it Europe, it would be packed. What a beautiful ride!

Sharda was taking as many photos as Jim and I were so it was inevitable that we'd strike up a conversation. I love meeting fellow travelers and hearing their stories. As much as I enjoy our life afloat, it's great to get away from the yachtie scene sometimes.

The ride terminated at a dirt lot in the town of Fierze. The ferry dropped its loading platform 1.5 meters below the lot which looked impossible for the cars to clear until the crew pulled out shovels and recontoured the shoreline.

A pretty drive through farmland and foothills led to Tropoja's administrative center, Bajram Curri, which was built during communism and named after another hero who fought against the Ottoman rule. In the shade of a tree Niku popped the hood and let his overheating radiator take a break before adding more water. He pointed to the school he attended as a child as we walked to an air-conditioned restaurant for lunch. I couldn't figure out if his dad knows everyone or is just really friendly.

At a fork in the road Niku steered left towards the Valbona Valley. The road runs alongside the clear, pale blue Valbona River which cuts through narrow gorges and tumbles past jumbled boulders.

Niku stopped for us to take photos of a footbridge crossing the Valbona River. A lady wearing boots and carrying a stick approached. "Miradita, good afternoon," I said, holding out my hand to shake hers. Her smile and warm eyes were instantly likable. "Bukur, beautiful," I said, waving my arm towards the mountains. She nodded, still smiling, and said a lot of words. Holding my arm as we walked back across the bridge, she said more things then kissed me good-bye. I didn't feel very threatened here.

Valbona Valley

Steep limestone peaks void of any vegetation rise above the folded mountains surrounding the Valbona Valley National Park in the Albanian Alps. A 400 meter long glacier hangs beneath a saddle, and a riverbed of rounded rocks flows through the wide, green valley.

Valbona Valley was a popular holiday spot until Albania's civil unrest began in 1997. Remains of the state-owned hotel still stand amid new construction. Most visitors are Kosovars as it's easier to reach this gorgeous location from Kosovo than from anywhere in Albania. With two meters of snow annually and no community services, store, or school, residents leave before the first snowfall and return in the spring.

We stayed the night in the Tradita farmhouse and had a tasty traditional meal of tender roasted goat meat, salad, and fried cornbread drenched in cheese-water. Flatbread with herbs topped with yogurt was a yummy dessert. While we were eating, Niku's father pulled out a bottle of homemade grappa and poured small glasses. Even the proprietor joined in for a toast. Gzuar!

Across the field from Tradita is a bunker built of stone. Further down the road is a concrete one. Sometimes people crush the bunkers to get the metal from them, but mostly they just remain part of the landscape.

The following morning we drove back down the valley to the fork in the road. This time we headed to Babine where Niku's father and uncles own land.

Pavement turned to dirt and switchbacked up a hill. When we reached a stream crossing, Niku said the road used to end there. Jim and I were happy for the extension. It's funny to think that real estate agents would not drive their shiny new AWD sport utes up our paved driveway in Mammoth when Niku's older Mercedes RWD conquered this steeper, rutted road just fine.

The house was built 60 years ago and the family is rebuilding it. High above a fertile valley, it's a peaceful location with several different kinds of fruit trees and a garden. The tiny plumbs were some of the best I've ever tasted.

Niku's father is one of 10 children, most of whom still live in the area. He was hesitant to stop at one sister's house for fear of offending the others. As we drove down from the house some relatives were waiting on the road to see him. Guess he didn't sneak in after all.

We looped through Kosovo on our way back to Shengjin. How cool is that? A line of cars was stopped off to the side but Niku drove past them, right up to the gate. He and his dad talked to the two guards who let us through after checking our passports.

Most families in northeastern Albania have relatives across the border in Kosovo. U.S. presidents Clinton and G. W. Bush are well-liked here. Clinton went to bat for the Albanians fighting Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War, much to the chagrin of other NATO countries, and Bush recognized Kosovo after they declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Several times during our trip we saw American flags flying along side Albanian or Kosovar flags.

During communism, the leader of Kosovo, Tito, let citizens leave the country. Many went to Western Europe to study and work. Now some have returned to invest in their homeland. They have money, unlike Albanians whose leader, Hoxha, did not allow people to leave their communities.

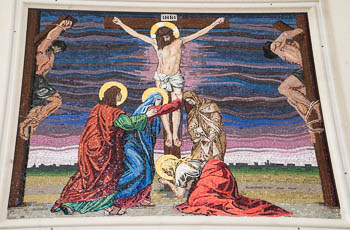

We stopped at St. Paul's church in Gjakova, Kosovo. The interior is light and bright and the stations of the cross are beautiful mosaics. I was happy to be there because it was my Aunt Rose's birthday and she was a devout Catholic. She would have been 104.

A line on the hillside marks the border between Kosovo and Albania.

We went up and down a lot of hills in 2 days. Several were 10% grades and Niku's Mercedes overheated several times. But the good thing about Mercedes' is that they can do that and nothing is ruined. In fact, durability is the reason Mercedes dominates the roads in Albania. With no private car ownership during communism, and little money for repairs now, people buy whatever year Mercedes they can afford.

Because Jim liked grappa so much, Niku invited us to his wife's parents' home to learn to make it. Her father has several kumbulla (plumb) trees and a homemade still.

Nazmi Bisha and his twin sons collect all the kumbulla that fall from the trees. They throw them in several 55 gallon drums and let them ferment for at least two weeks. When he's got a spare 12 hours, Nazmi makes 4 batches of grappa per drum.

He pours the fermented kumbulla into a pot, then adds a little water to keep it from sticking. Next he puts the top on which is the same size, just opposite shape, as the pot. It has to fit just right before he seals it with bread dough. Then he puts the pipe on that transfers the vapor to the cooling tank. These are sealed with bread dough as well.

A fire is built beneath the pot to boil the kumbulla which forms a vapor that flows through the pipe. The vapor cools as it descends through the cooling tank which creates the grappa that slowly pours out the small pipe at the bottom.

The strength of the grappa is measured by the size of the flame it makes.

While the second batch of grappa was brewing, Niku took us to the river to see how his wife's uncle fishes. A large, square net is attached at all four ends and lowered to the bottom of the river. When it is raised, fish are caught and tumble down to the center where a bucket and net captures them. Niku caught a nice sized krap (carp) which Benisa, his wife, cooked and served with the elaborate and delicious meal she prepared for us - a tomato, cucumber, onion salad, homemade cheese, pasta with mussels, two types of meat, and heaping plates of delicately spiced sardines. And grappa. Lots of grappa. Nazmi sent Jim home with a freshly brewed bottle with instructions to put a cinnamon stick inside until the liquid turned dark.

Benisa's family lives on farmland near the estuary and her dad works at the Kune Vain Nature Reserve. I asked her if she'd gone there as a little girl and she said, "Yes, we played here all the time."

Faleminderit Niku and your family for your kindness, hospitality, delicious jam, figs, plumbs, tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, grapes, salted peppers in the big plastic bottle, and grappa.

Faleminderit Albania. We will miss you.

Yachtie Information:

It's 42 miles from Durres to Shengjin. The port has been redone since the information in the Imray guide. We never saw less than 5.7 meters outside or 7 meters inside the harbor which has been redone since the 2012 version of the Imray pilot. The dock is not perfect for a boat less than 50', but you can make it work with fenders and springs. It's a good place from which to visit Lake Schodra and the castle at Lezha. The agent, Frrok Frroku, can be reached at Orion.shipping.agency@gmail.com. Don't worry if he does not reply. Best to call him at 00355682035531. As it is a working port, expect to be allowed to stay two days.

The best Pilot Book to have is: 777 Harbours & Anchorages, Eastern Adriadic - Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro & Albania by Sonia Florian, Dario Silvestro and Piero Magnasbosco, 2014 version. Each page is a true nautical chart - North up - featuring meridians and parrallels. The anchorages show directions of wind protection and contour lines. The author provides a keen insight into the country and its people, better than the Bradt Albania (non-sailing) guide book. The Imray Adriatic Pilot, by Trevor and Dinah Thompson, has more waypoint errors than we have seen in all other Imray publications combined.

Quote from the Imray guide: We have been unable to visit Albania ourselves because of the political and social situation. 2012 Version.

Quote from the 777 guide: We arrived in Durres... It was the best decision in our lives: Albania became our great passion. This is the reason why this pilot book was written.

Go to August 2015 Part Four - Montenegro

Go to Previous Page: Central Albania

Go to Previous Page: Southern Albania